A sloth bear after digging for termites and ants © Saurabh Shukla

October 12 marks World Sloth Bear Day, a day established to raise awareness on the conservation of sloth bears, a species native to India, Nepal and Sri Lanka. These animals, named for their slow-moving habits and long curved front claws, are considered among the most infamous in the region, despite only feeding on fruit, termites and ants.

Sloth bears may have evolved their formidable fighting behaviour to survive among carnivores such as tigers and other bears. Known for their explosive charges when threatened, sloth bears were responsible for more negative human–wildlife interactions in the region between 1950 and 2019 than any other large carnivore (*).

Threats from habitat loss and human–wildlife conflict have led to a declining population now estimated at fewer than 20,000 globally, resulting in the species being categorised as Vulnerable on the IUCN Red List. Its dwindling numbers are concerning not only for the species, but also for the ecosystems it supports—the bears play a key role in dispersing fruit seeds and managing termite populations. Understanding the species’ behaviour, particularly its response to perceived threats, is key to mitigating conflict and improving safety for both humans and bears.

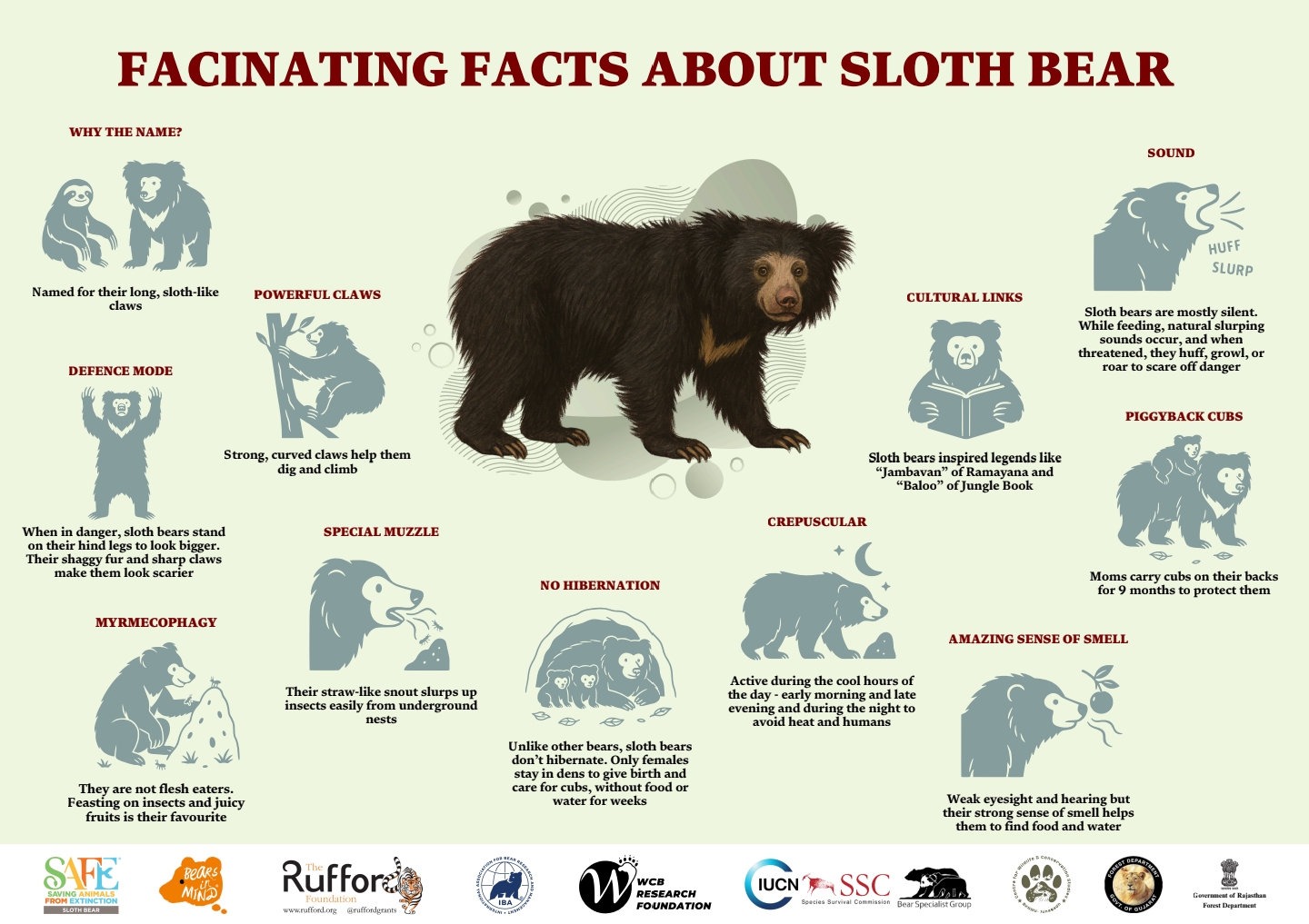

Infographic: Facts about sloth bears

Infographic: Facts about sloth bears

Sloth bear expert, Nishith Dharaiya, has been studying sloth bears since 2008. Currently Director of the Center of Excellence for Wildlife and Conservation Studies at the Bhakta Kavi Narsinh Mehta University, Junagadh, India, Nishith’s efforts to raise awareness of the species and its conservation have gained attention from forest officials, policy makers and several international conservation organisations.

Back in 2008, Nishith was awarded a Rufford Small Grant for his project titled ‘Evaluating Habitat and Human–Sloth Bear Conflict in North Gujarat, India – To Seek Solutions for Human-Bear Coexistence’. The project focused on studying the distribution of sloth bears and the nature of human–bear conflict in northeast Gujarat, with the aim of identifying strategies to promote peaceful coexistence between local communities and wildlife.

Initial research was followed up by two further Rufford-funded studies in 2009 and 2012, revealing human–bear conflicts in the region were largely driven by a lack of awareness among local communities about sloth bear behaviour, along with shrinking bear habitats in northeastern Gujarat. Similar challenges were identified in central Gujarat, where the forests remain unprotected yet support a significant sloth bear population—one whose distribution is still not fully understood.

“As part of our efforts, we have developed and designed awareness materials, communication strategies and tools to mitigate human–sloth bear conflicts in India”, explains Nishith. “One such tool invented by our team is the ‘Bear Deterrent Stick’, popularly known as Ghanti Kathi. Other initiatives include identifying and constructing water accumulation points in the forests to prevent sloth bears moving towards villages in search of water during the hot and dry season, and plantation patterns in which fruit bearing species are planted in clusters, making food available throughout the year.”

A sloth bear sniffing the ground in search of ant nests © Vickey Chauhan

A sloth bear sniffing the ground in search of ant nests © Vickey Chauhan

Looking ahead to the future of sloth bear conservation, Nishith says, “I would like to prepare a secondary line of young researchers and conservation professionals in the region to enhance sloth bear research and conservation on a larger scale. In partnership with the International Association for Bear Research and Management (IBA), I am conducting training sessions in various states of India for young researchers and frontline forest staff, focusing on bear research, monitoring and addressing human–sloth bear conflicts. Additionally, I want to continue my research and conservation work on sloth bears in the forests of central India, especially those not protected or designated as National Parks or wildlife sanctuaries. I am also planning to initiate science-based conservation actions by engaging local community and forest officials.”

As we mark World Sloth Bear Day, it’s a powerful reminder of the urgent need to protect this unique and often misunderstood species. Although significant challenges remain—from habitat loss to human–wildlife conflict—the conservation efforts underway in the field offer real hope.

(*) Source: A worldwide perspective on large carnivore attacks on humans | PLOS Biology